Weekly reading 1

Mar 29, 2020- slack

- wework

- propaganda

Twitter thread from its CEO on the surge of Slack usage:

More signs of demand surge. 1,597 days after hitting 1M simultaneously connected users in Oct ‘15 we pass ten million. 6 days later: 10.5M, then 11.0M. Next day, 11.5M. This Monday, 12M. Today 12.5M.

FaceBook also sees surge in the usage of WhatsApp and Messenger. But in the same post they predict downward trend revenues-wise, because however demand (app usage) increases, supply (advertisers) actually decreases in such a turbulence time.

WeWork’s stock went down some more:

Now is the bad time. WeWork is not a unique hilarious catastrophe anymore; it is just a sad catastrophe like so many other businesses. If your city shuts down, if everyone fears the plague, if office workers are told to work from home, no one will be coming to a WeWork, just like no one is going to restaurants or movie theaters.

No one is going to lots of other offices either, but it’s a bigger problem for WeWork than for most office landlords because so much of its business model was about giving tenants flexibility. If you are a big company with a multi-year lease on 10 floors of a midtown office building, you’re probably not going to stop paying rent just because your employees are working from home for a few months. When things recover, you’ll want that space back; your stuff is there; you signed a long-term commitment. If you are a startup renting a few desks month-to-month at a WeWork, sure, stop doing that for a while, why not. “We pioneered a ‘space-as-a-service’ membership model,” said WeWork, back in the good times. “Across our global portfolio of locations, we offer individuals and organizations the flexibility to scale workspace up and down as needed, with the ability to consume space by the minute, by the month or by the year.” If you offer organizations the flexibility to scale workspace up and down as needed, they will all scale it down in a pandemic.

As a result even Softbank, the major investor of WeWork, doesn’t want to save it now.

The goddess: a Vancouver Valentine of love, lawsuits, mansions and millionaires:

“Thank god [we] met each other unexpectedly,” Rao told Li via WeChat a few days after first laying eyes on her. “You will add so much lustre to my life. I’m grateful for having you. I love you!”

[…]

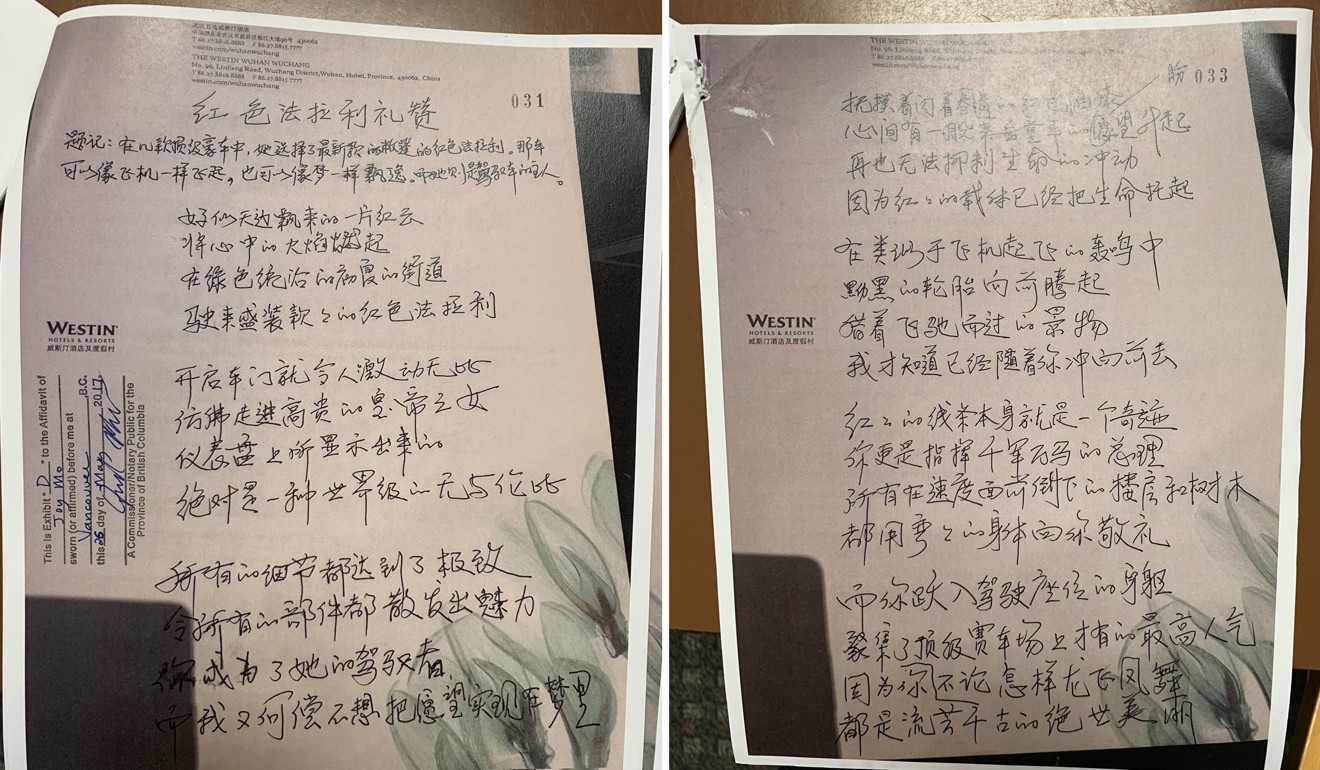

Huang, a member of the Canadian Chinese Writers’ Association, immortalised his devotion in a seven-stanza Chinese poem, titled Tribute to Red Ferrari. Instead of ending up as a treasured keepsake, it was filed as evidence by Li’s lawyers.

Both Rao and Huang fell in love with Li and spent giant amount of money on her, but ended up both feeling scammed. Meanwhile Rao is already married to another woman back in China. Then they filed many lawsuits to each other, both in Canada and China. It’s also covered in Chinese media with fewer details: 科陆电子谈董事长卷入跨国重婚案传言:个人事项对公司无影响.

How China is Influencing YouTubers into Posting State Propaganda:

Franco isn’t a typical Chinese name. Which made the email that J.J. McCullough, a Canadian YouTuber and conservative columnist, opened last May all the more peculiar. “Hi McCullough, Just watched your videos, and we thought it would be a great to place our content, we wonder if you want to help us upload this video to your youtube channel? And for that, we will support your youtube channel for $500” [sic] read the email. Attached was a video which can charitably be described as pro-Chinese government content; a less generous description might be clumsy propaganda.

The claim is Chinese propoganda groups leverage Americans to post pro-Beijing content to influence Chinese. The content itself is total consperacy stir-up, like this video arguing coronavirus is from U.S. I mean sure people can argue he is as independent as he says so. The interesting thing is the pattern emerges that looks like only one kind of voice can really survive and succeed in China, even for foreigners.

Back to home